Pharmaceutical Supply Chain Reinvention

15 Jan

Majority of pharmaceutical companies are persisting with decade old processes and routines. They have transactional relationships with suppliers, lack of concerted efforts to progress ahead, and no vision to reap productivity rewards. The reasons for continuing with these traditional practices include tax regimes, regulatory hurdles, and stable revenues from customers dependent on existing industry offerings.

Disruption—spurred by technological Innovation, fluctuating customer demand patterns, and more agile and creative competitors—has forced the pharmaceutical sector to think of ways to face these challenges, survive, and thrive. One of the strategic response to this competitive disruption—by leading manufacturers—is to reexamine their manufacturing operations, embracing agile principles, reducing costs, revolutionizing procurement and distribution functions, and striving to achieve Operational Excellence. Above all, they view their supply chain not as a cost center, but as a source of Competitive Advantage.

The increasing influence of generic drugs is another challenge for large multinational pharmaceuticals. In the past, multinational companies (MNCs) dominated the market owing to possessing a number of high-market drugs protected under patents. Patent protection afforded them the leverage to set high prices on each product. The scenario is fast changing. Expiry of high-market drugs patents is creating a huge opening for generic competitors and the space is widening compared to the past.

In the past, pharma manufacturers were able to counter the threat to generic competitors by developing new drugs. However, this is becoming difficult and the new drugs pipeline is shrinking with time. R&D expenditure has continuously gone up, however, drug approval from the authorities has not kept paced with it. It has rather declined, straining the MNCs further.

Other disruptive factors include newer distribution methods, public health plans favoring generic drugs over proprietary ones due to cost effectiveness, the newer internet / mail delivery options displacing traditional pharmacy dispensing options. Pharmacy chains—e.g. Walgreens—have given a leverage to the retailers to negotiate reduction in medicine prices where again generics have an edge over MNCs.

Moreover, the trend of drugs purchased through a formal tender process is increasingly gaining acceptance, adding to the difficulties of large pharma manufacturers. Additionally, strict regulations are minimizing the cost benefits that MNCs traditionally enjoyed in the past.

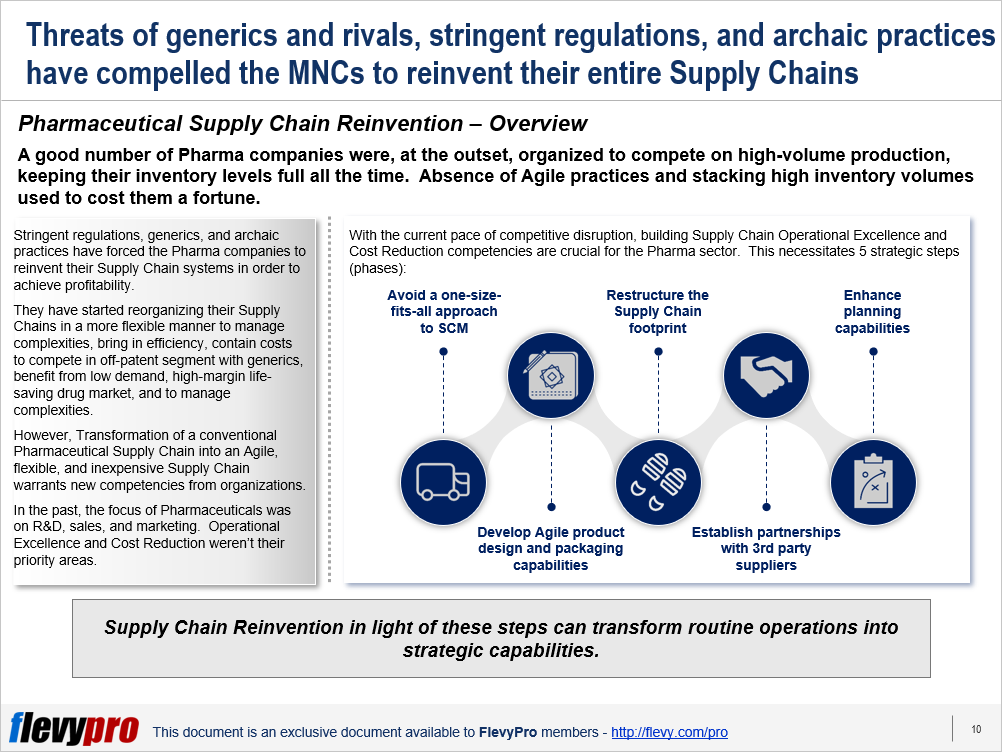

All these factors have forced the pharma companies to reorganize their Supply Chains in a more flexible manner to manage complexities, bring in efficiency, and contain costs to compete in off-patent segment with generics.

Reorganization of a conventional pharmaceutical Supply Chain into an Agile, flexible, and inexpensive Supply Chain warrants developing Operational Excellence and Cost Reduction competencies. This necessitates 5 strategic steps (phases):

- Avoid a one-size-fits-all approach to SCM

- Develop Agile product design and packaging capabilities

- Restructure the Supply Chain footprint

- Establish partnerships with 3rd party suppliers

- Enhance planning capabilities

Let’s discuss these steps in detail.

Step 1 – Avoid a One-size-fits-all Approach to SCM

Large pharma MNCs typically maintain the Supply Chain of all of their drugs with a single strategy of retaining high inventory and service levels. Such a strategy can only work for products having a high profit margin, in a static environment. It is not suitable for low-margin products, contrasting environments, and does not take into account fluctuations in demand patterns. An appropriate approach is to implement a multiple Supply Chains model based on individual products and markets.

Step 2 – Develop Agile Product Design and Packaging Capabilities

The 2nd step in Pharma Supply Chain Reinvention involves quick distribution of different versions of products to markets based on demand. For low-margin products with high demand volatility, the Supply Chain Management Strategy should be to employ Pack-to-Order system. The Pack-to-Order approach involves developing a version of a product that could be timely dispatched to several markets of varying demand across the globe. This approach coupled with Postponement Strategy—where products are packed to order during later stages of production based on regional demand—assists in trimming down the inventory, reducing complicatedness, and enhancing Supply Chain nimbleness to demand volatility.

Interested in learning more about how to reinvent your Pharmaceutical Supply Chain? You can download an editable PowerPoint on Pharmaceutical Supply Chain Reinvention here on the Flevy documents marketplace.

Do You Find Value in This Framework?

You can download in-depth presentations on this and hundreds of similar business frameworks from the FlevyPro Library. FlevyPro is trusted and utilized by 1000s of management consultants and corporate executives. Here’s what some have to say:

“My FlevyPro subscription provides me with the most popular frameworks and decks in demand in today’s market. They not only augment my existing consulting and coaching offerings and delivery, but also keep me abreast of the latest trends, inspire new products and service offerings for my practice, and educate me in a fraction of the time and money of other solutions. I strongly recommend FlevyPro to any consultant serious about success.”

– Bill Branson, Founder at Strategic Business Architects

“As a niche strategic consulting firm, Flevy and FlevyPro frameworks and documents are an on-going reference to help us structure our findings and recommendations to our clients as well as improve their clarity, strength, and visual power. For us, it is an invaluable resource to increase our impact and value.”

– David Coloma, Consulting Area Manager at Cynertia Consulting

“FlevyPro has been a brilliant resource for me, as an independent growth consultant, to access a vast knowledge bank of presentations to support my work with clients. In terms of RoI, the value I received from the very first presentation I downloaded paid for my subscription many times over! The quality of the decks available allows me to punch way above my weight – it’s like having the resources of a Big 4 consultancy at your fingertips at a microscopic fraction of the overhead.”

– Roderick Cameron, Founding Partner at SGFE Ltd